The

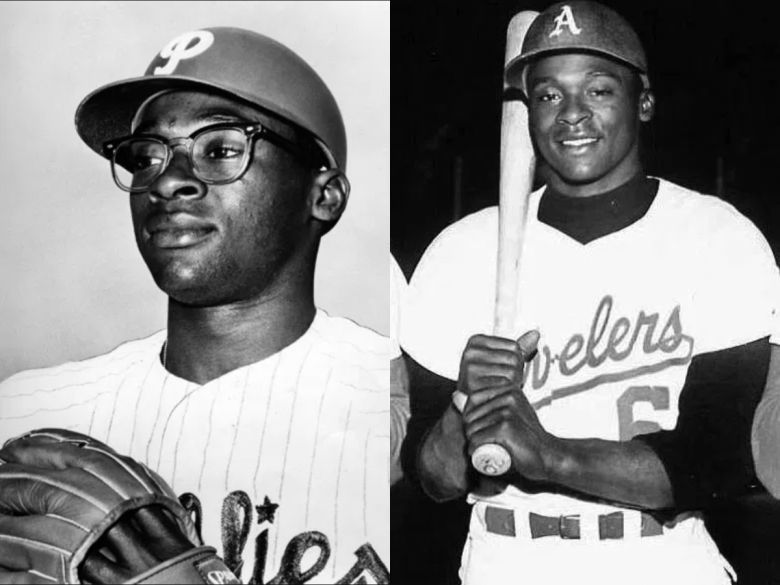

Philadelphia Inquirer has an emotional story this week (paywall) about

Dick Allen

, the one-time Arkansas Traveler who was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in December, and the efforts of his son to tell his dad’s tale some six decades later.

Allen, the first Black position player in Travelers’ history, did not want to come to Little Rock in 1963. The city was less than a decade removed from the Central High School integration crisis, and Jim Crow still ruled the day. Allen, who had never visited the South, asked the Phillies not to send him.

As the Inquirer story explains, Allen’s fears about life in Little Rock were reinforced as soon as he arrived.

“When Allen arrived in Arkansas, one of the first things he saw was a man at the airport carrying a sign that read, ‘LET’S NOT NEGRO-IZE OUR BASEBALL.’”

Things did not improve much for Allen once the season started. The Inquirer writes:

It was a sold-out crowd for the Travelers’ first game that year, and people picketed Allen’s presence. To get into the stadium, he had to walk by the same sort of racist signs he’d seen at the airport. […]

“I remember wanting to show those Little Rock folks my strength,” Allen wrote. “My inner strength.”

He left the game that night later than all of his teammates. His car was alone in the lot, with a note on the windshield that said DON’T COME BACK AGAIN N —

“There might be something more terrifying than being Black and holding a note that says n — in an empty parking lot in Little Rock,” Allen said in Crash. “But if there is, it hasn’t crossed my path yet.”

While his single season with the Travelers was a success — Allen was voted the team’s most valuable player after hitting 33 home runs and slashing .289/.341/.550 — he never felt comfortable in the city. When he was promoted to Philadelphia in September 1963, the story says, “he immediately sold the car he drove to his home games at Travelers Field” because he “wanted to sever any connection to Little Rock, the place where he’d spent a lonely five months.”

The Inquirer story presents a lot of this information through the eyes of two people who knew Allen: fellow Major League Hall of Famer

Ferguson Jenkins

and Dick Allen, Jr. Before his father died in 2020, the younger Allen tried to talk him into a road trip back to Little Rock, to see some of the places where his father “had been an unwitting trailblazer in hostile territory.” The elder Allen said it would be “like walking through a graveyard” and would not go.

In April, some five years after Dick Allen’s death in 2020, his son made the trip anyway. He attended a Travelers game at Dickey-Stephens Park, where he was joined by Jenkins, who played with Allen in Little Rock in 1963. They toured the Little Rock neighborhoods where Dick Allen lived and played baseball during that difficult summer, including the house where Allen rented a room from the family of Little Rock Nine student Melba Patillo Beals. They visited Central High School and Doe’s Eat Place and the parking lot where Ray Winder Field once stood.

One reason for the trip was Allen’s upcoming induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. (The ceremony will take place on July 27.) Another was to film footage around Little Rock for the younger Allen’s forthcoming documentary, “My Father, Dick Allen,” which is scheduled to be released next year.

But reading the Inquirer story, one gets the sense the trip was about more than that. It was, at its most basic level, about a son trying to know his father more completely. Dick Allen hated his time in Little Rock; seeing the place in person was a way for Dick Allen, Jr., to contextualize and understand his father’s feelings and experiences. Here’s more from the Inquirer:

Allen used to tell his son that he would hate to be in his shoes. He knew it would be difficult to bear his name and follow in his footsteps.

But that April evening, with a baseball in his hand and his father’s teammate by his side, Allen Jr. didn’t feel it as pressure. When he boarded the plane to leave Arkansas the next day, he would look out the window and wonder how Allen had survived what he went through.

But he also thought about bringing his son, Richard Allen III, back to Little Rock someday. He hopes to take him on a tour — hopefully the Ray Winder Field scoreboard will still be standing — and show him the history. And, of course, they’ll take in a Travelers game together.

We wrote about Allen

shortly after news broke of his election to the Baseball Hall of Fame. The Encyclopedia of Arkansas

also has a detailed entry

about Allen and his time in Arkansas. But perhaps the inimitable Ernie Dumas put it best when

wrote about Allen in 2020

, shortly after the ballplayer died.

We write about our community’s brief encounter with the young man because, in this winter of our discontent, Dick Allen, or “Richie” as the player’s owners insisted that he call himself when he was in Little Rock and a little beyond, reminds us of the barely diminished vexation of racial resentment that has always beset the country, our state and our community, and still does. We use resentment rather than prejudice because most of us do not want to be called prejudiced.

It’s dragon-slaying time!

In a time when critical voices are increasingly silenced, the

Arkansas Times

stands as a beacon of truth, tirelessly defending the fundamental rights and freedoms within our community. With Arkansas at the epicenter of a sweeping culture war affecting our libraries, schools, and public discourse, our mission to deliver unflinching journalism has never been more vital. We’re here to “slay dragons” and hold power accountable, but we can’t do it alone. By contributing today, you ensure that independent journalism not only survives but thrives in Arkansas. Together, we can make a difference — join the fight.